Sprott’s Hill Ancient Mound Site

Location and Historic Designation:

Coordinates: 40°54′49″N 82°21′42″W

West side of Township Road 1193 between Bailey Lakes and Ashland, in Clear Creek Township, Ashland County, Ohio, USA

National Register of Historic Places #76001363 (1/31/1976)

Dates 499-0 BC; 500-999 BC; 1000-1499 BC

There are countless ancient mounds and earthworks throughout the state of Ohio. Some are estimated to date back to around 1500 BCE, while others are dated around 300 BC – 200 AD, and may have been in use as recently as 1650 CE. The mounds vary in structure with the most common being conical, dome, platform, and effigy mounds and each were used for different purposes. Some mounds were utilized as burial sites, while others are believed to have been used for religious and ceremonial activities, and others appear to have been constructed as forts or lookouts. Most ancient mounds that once existed in Ohio have since been plowed down by farmers or developers, and many were looted of the human remains and sacred cultural objects buried within them. The mounds that remain today are typically designated as a National Historic Landmark, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, or designated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. Some of the larger and more elaborate sites such as The Great Serpent Mound are used as educational sites or cultural centers, while others sit inconspicuously in the middle of community. It is not uncommon for ancient mounds to be found on residential property, as is the case of Sprott’s Hill.

While living in rural Ohio for a brief time, I learned that there was an ancient mound site called “Sprott’s Hill” on my neighbors’ land. Intrigued, I began researching Sprott’s Hill. Through digitized historical publications, a visit to the site, and information obtained from the Ohio History Connection, I pieced together a fascinating history of the mound site. I find that the story of Sprott’s Hill serves as a unique lens through which to view several significant events in American history, settler-indigenous relations and the ways in which people have interacted with the same land over time. The following is a summary of what I found.

The History of Sprott’s Hill

Sprott’s Hill, located in Clear Creek Township, Ashland County, Ohio, is the former site of two ancient burial mounds that were destroyed by farmers’ plows in the late nineteenth-century. The hill itself is a glacial kame that was formed from large gravel deposits left behind by melting glaciers that once covered the region.

Before Europeans arrived in the area, Clear Creek Township was the hunting ground for several tribes of Native Americans, including the Delawares, Senecas, Wyandotte’s, Mingoe’s, Mohegan’s, and Ottawa’s. (Ashland County Commissioner, 1-2). By the time of the Revolutionary War, the Continental Army established forts within the Indian Territory.

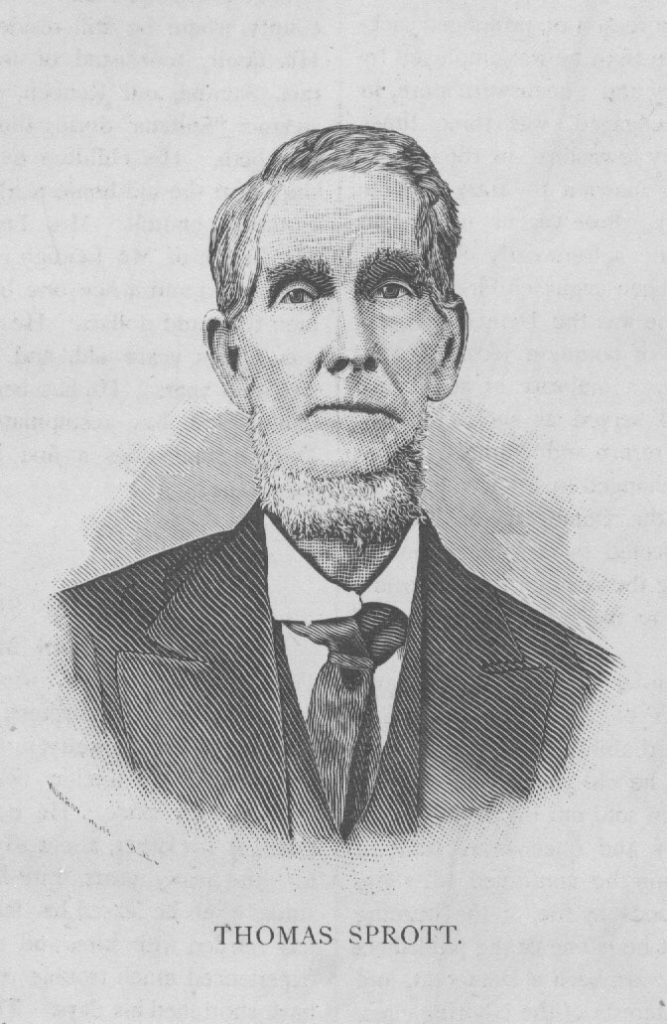

Thomas Sprott

In 1783, a seventeen year old Thomas Sprott from Pennsylvania joined the notorious ‘Indian Fighter’ Captain Samuel Brady to enter the Indian Territory. The plan was to travel from Fort Macintosh toward the upper Sandusky to locate an encampment of the natives.

The group of about 8 men, including young Sprott, left Fort McIntosh and ascended the Beaver River to the mouth of the Mahoning River. During the journey, one of the men shot a bear and the group roasted and ate the bear for supper that evening. During the night, one of the men became very sick and by morning was unable to proceed with the group’s mission. It was agreed that he should return to Fort McIntosh and the duty fell upon young Thomas Sprott to accompany him back to the Fort. By 1793, Thomas Sprott was employed by the Government to carry the mail from Fort Legionville, the winter quarters of General Wayne, to Fort Franklin on the Allegheny River in Pennsylvania. By 1795 he had married and bought a farm in Darlington, Pennsylvania.

Decades later, in 1823, a widowed single father, Thomas Sprott returned to the Ohio wilderness to settle on a farm on Section 35 of Clear Creek Township in Ashland County. On his land, Sprott discovered a hill that stood about 125 feet above the surrounding valleys.

The surface on the top, from north to south, was about 125 feet long, and from east to west, about 100 feet. The top of the hill was level, with the exception of two mounds that stood about 24 feet apart, nearly 4 feet high, and 30 feet at the base of each. Large trees that were growing upon and around the hill appeared to be centuries old. There was also a small trench around the south of the mound that remained for years after Sprott arrived. There was also a stone wall around the perimeter of the hill that was later plowed down some time in the late 19th century.

According to the story, Sprott dug into the south mound one day and discovered a large coffin built of flat stones and topped with numerous funerary objects or ‘Indian relics’ as they were referred to. Reportedly, within the coffin, were the remains of six to eight humans covered in “a peck of Indian red paint.” Sprott reportedly left everything as he found it and refilled the grave (Knapp, 1863).

Sprott died in 1839, and according to his wishes, he was buried in one of the mounds. His son William was also buried in one of the mounds in 1845. However, their remains were moved to the nearby Savannah Cemetery in 1880 after new owners purchased the land (Shopbell). I have found no reports of what happened to the human remains and funerary objects that were originally buried in the mound before Sprott, and no mention of whether they were also relocated to the Savannah Cemetery at that time.

Present Day

Today, the property on which Sprott’s Hill sits is split between two Amish families who use the hill as their cow pasture. Around the base of the hill broken stones are strewn about. Perhaps, they were part of the stone wall that reportedly stood. However, they could be discarded there from another source at a later date and have no link to the stone wall. This was just my observation during my visit in 2015.

Who were the Moundbuilders at Sprott’s Hill?

The National Register dates the construction of the burial mounds ranging anywhere from 1499 BC-499 BC, which was during the Glacial Kame Culture period. The Glacial Kame Culture occupied southern Ontario, Michigan, Ohio, and Indiana from around 8000 BC to 1000 BC. Their name is derived from the practice of burying their dead atop glacier-deposited gravel hills. Among the most common types of artifacts found at Glacial Kame Culture sites are shells of marine animals and goods made from copper ore.

More precisely, the group who constructed the burial mounds on Sprott’s Hill were likely part of the Red Ocre Culture. A series of other archaeological sites located in the Upper Great Lakes, the Greater Illinois River Valley, and the Ohio River Valley have been identified as Red Ochre burial complexes, dating from around 1000 BC to 400 BC. In The Red Ocher Culture of the Upper Great Lakes and Adjacent Areas, the Red Ochre Culture is:

“a term used to designate a phase (probably of Woodland pattern) which is characterized by beautifully made leaf and truncated leaf-shaped projectile points, crude pottery, copper implements and ornaments, simple burials in flexed position frequently associated with caches of artifacts, and profuse amounts of red ochre (Ritzenthaler and Quimby, 1962).”

Interestingly, another group referred to as The Red Paint People who flourished between 3000 BC and 1000 BC on the east coast also used ochre in their burials suggesting that the practice started in the east and spread westward (Alward and Atherton, 2007). In fact, the use of red paint in burials was practiced in locations around the world, including various Neolithic sites in Anatolia, and have also been discovered in Paleolithic sites in Europe estimated to be as old as 25,000 years, and in sites Australia estimated to be around 40,000 years old.

What happened to the Moundbuilders?

There are different theories about why the Moundbuilders of the Midwest seemingly disappeared. Some believe that they were decimated by epidemics brought on by colonists. Others theorize that they were decimated by an epidemic brought on from trading with other native groups from the south, as far as Mexico, long before the colonists arrived. Some believe that the Moundbuilders weren’t decimated at all, but that they migrated west when the colonists started to arrive on the east coast. Some believe that they migrated much earlier. While there was indeed migration from the east coast to the midwest, some theorize that at least some of the Moundbuilders remained in the area. This seems likely since there are native tribes that claim to be the direct descendants of the Moundbuilders.

At the time that the colonists came in contact with the indigenous tribes, some natives claimed that they did not know who built the mounds and that they were built by the people who were there before them. In some accounts, the natives referred to the Moundbuilders by various different names, including Tallegewi, Allegewi, and The Prarie People, all of which are identifiable as other Native American tribes.

NAGPRA

In any discussion about ancient mounds in the U.S., it is important to note the importance of the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). NAGPRA requires that human remains of any ancestry “must at all times be treated with dignity and respect.” The Act requires human remains and other cultural items, including funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony removed from Federal or tribal lands be returned to lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations. It requires museums to develop an effective process of returning these objects to the claiming indigenous tribes. This involves the transfer of millions of objects held in museum collections around the U.S. In the case of a legal transfer of human remains and funerary objects, the claiming tribe will be able to hold a ceremonial reburial on tribal land.

Since the passing of NAGPRA in 1990, some progress has been made, but there have been challenges in the process leaving hundreds of thousands of Native American human remains and cultural items yet to be repatriated. Many museums lack the policies, funding, and staffing necessary to follow the law and repatriate their collections. In other cases, the claiming tribe may not have the resources to physically transfer at the time of the legal transfer. There is also an issue of identifying what tribe the objects belong to since there were migrations and further displacement after the Indian Removal Act of 1830. In these cases, the last known indigenous tribes can take legal possession of the objects.

As for the human remains and funerary objects that were buried in the mounds at Sprott’s Hill, I have not found any institution that claims to hold the objects. Many of the mounds in the area were looted and the objects were sold or destroyed in the process. It may never be known what happened to the Moundbuilders of Sprott’s Hill.

References cited and for further reading:

Alward, Brian, and Morgan Atherton. (2006). Time Range. The Red Paint People. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20060909174742/http://www.usm.maine.edu/gany/webaa/newpage3.htm.

Ancient Earthworks in Ohio in The Miscellaneous Documents of the Senate of the United States. (1878). 263-266. Washington: Government Printing Office. Ebook. Accessed November 10, 2018.

Ashland County Commissioner. Historical Sketch of Ashland County. 12. https://www.ashlandcounty.org/commissioners/files/history.pdf.

Baughman, A. J. (1909). History of Ashland County, Ohio. S.J. Clarke Publishing Company.

Brose, D., & Greber, I. (1982). The Ringler Archaic Dugout from Savannah Lake, Ashland County, Ohio: With Speculations On Trade and Transmission in the Prehistory of the Eastern United States. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology, 7(2), 245-282. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20707893.

Fowke, Gerard. (1902). Structure and Contents of the Mounds in Indians of North America.

Hill, Newton. (1880). History of Clear Creek Township. History of Richland County, Ohio. 651-653. A.A. Graham & Co., http://www.ashlandohio.pa-roots.com/Hist-CC.html.

Hinojosa, Javier. Mayan Red Queen. Spartan Ideas. MSU. http://spartanideas.msu.edu/2014/05/22/investigating-red-colored-bones-in-mesoamerica/photo.

History of Richland County 1807-1880. (1880). Retrieved from http://archive.org/stream/

Howe, H. (1902). Historical collections of ohio: An encyclopedia of the state: History both general and local, geography with descriptions of its countries, cities and villages, its agricultural, manufacturing, mining and business development, sketches of eminent and interesting characters, etc. Cincinnati, Ohio: The State of Ohio.

Knapp, H. S. (1863). A history of the pioneer and modern times of Ashland County: From the earliest to the present date. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co. https://www.forgottenbooks.com/en/download/AHistoryofthePioneerandModernTimesofAshlandCountyFromtheEarliesttothePresentDate_10527100.pdf

Merrill, John. (2018). Ohio’s 3 Ancient Mound Building Cultures. Touring Ohio. Ohio City Productions, Inc. http://touringohio.com/history/3-mound-builder-cultures.html.

Milner, George R., (2004). The Moundbuilders: Ancient People’s of Eastern North America. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nagpra/index.htm

Natmusdk. (2018). A woman and a Child from Gøngehusvej / Why is Ochre Found in Some Graves? National Museum of Denmark. Retrieved 15 November, 2018, from https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-mesolithic-period/a-woman-and-a-child-from-goengehusvej/why-is-ochre-found-in-some-graves/.

Potter, Elisabeth Walton and Beth M. Boland. (1992). Guidelines for Evaluating and Registering Cemeteries and Burial Places. National Register Bulletin 41. Npsgov. Retrieved 15 November, 2018, from https://www.nps.gov/nr/publications/bulletins/pdfs/nrb41.pdf.

Ritzenthaler, Robert, E. and Quimby, George, I. (1962). The Red Ocher Culture of the Upper Great Lakes And Adjacent Areas. Fieldiana Anthropology 36:11. Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Natural History Museum.

Shopbell, Russ. Thomas Sprott. Ashland County Chapter of the Ohio Genealogical Society. http://ashlandohiogenealogy.org/historyashland/historyashland95.html.

Smith, Z. F. “Pre-Historic People of Kentucky.” Register of Kentucky State Historical Society 6, no. 17 (1908): 17–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23366445.

Smithsonian Institution. Board of Regents, and United States National Museum. Annual report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution 1877. Smithsonian Institution, 1846. https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/annualreportofbo1877smit

Smithsonian Institution. Board of Regents, and United States National Museum. Annual report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution 1881. Smithsonian Institution, 1846. https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/annualreportofbo1881smit

Sprott’s Hill Mounds Site. (2018). Npsgov. Retrieved 15 November, 2018, from https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/76001363.

Wick, Sharon. (2018). Ashland County, Ohio History & Genealogy. Retrieved 15 November, 2018, from http://www.ohiogenealogyexpress.com/ashland/ashlandco_clearcreektwp.ht.