Iconoclasm

Religious syncretism

the fusion of diverse religious beliefs and practices.

Iconoclast

a person who destroys religious images or opposes their veneration

Iconoclast comes from the Greek word eikonoklastēs, which translates literally as “image destroyer.”

Serapeum

Serapeum were temples dedicated to the syncretic Greco-Egyptian deity Serapis, who combined aspects of Osiris and Apis in a humanized form that was accepted by the Ptolemaic Greeks of Alexandria.

Building the temple of serapeum in Alexandria, Egypt

Fourth century Egypt was a time when Christians, Jews, and pagans were living among one another in Alexandria, Egypt. There were several religious centers around Egypt, including several serapeum. Serapeums were temples dedicated to the syncretic Greco-Egyptian deity Serapis. The Serapeum of Alexandria was built by Ptolemy III Euergetes, and the statue of Serapis, for which the temple was built, was brought to Alexandria by Ptolemy I Soter who reigned from 304 to 282 BC.

![The Serapeum of Alexandria (VII)

The remains of the ancient site of the Temple complex of Sarapis at Alexandria. It once included the temple, a library, lecture rooms, and smaller shrines but after many reconstructions and conflict over the site it is mostly ground level ruins. by Iris Fernandez (2009)

copyright: 2009 Iris Fernandez (used with permission)

photographed place: Alexandria [pleiades.stoa.org/places/727070/]

Published by the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World as part of the Ancient World Image Bank (AWIB). Further information: [www.nyu.edu/isaw/awib.htm].](https://eqe.bnu.mybluehost.me/website_d506cb28/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/5B1FCCFB-CAE5-4001-8502-36FF2AB48642-1024x757.jpeg)

The origin of Serapis is in Ancient Greek and Egyptian mythologies, but Ptolemy I Soter is credited with inventing the new god, Serapis, in an effort to unite the religions and cultures of the Egyptians and Greeks. After seeing the statue in Sinopee, Turkey he brought it back to Alexandria. He claimed that he had been bidden to do so in a dream, and that “the statue hopped in the Alexandrian ship after the locals were unwilling to part with it.” When the statue arrived in Alexandria, two religious experts under the king declared the statue to be Serapis.

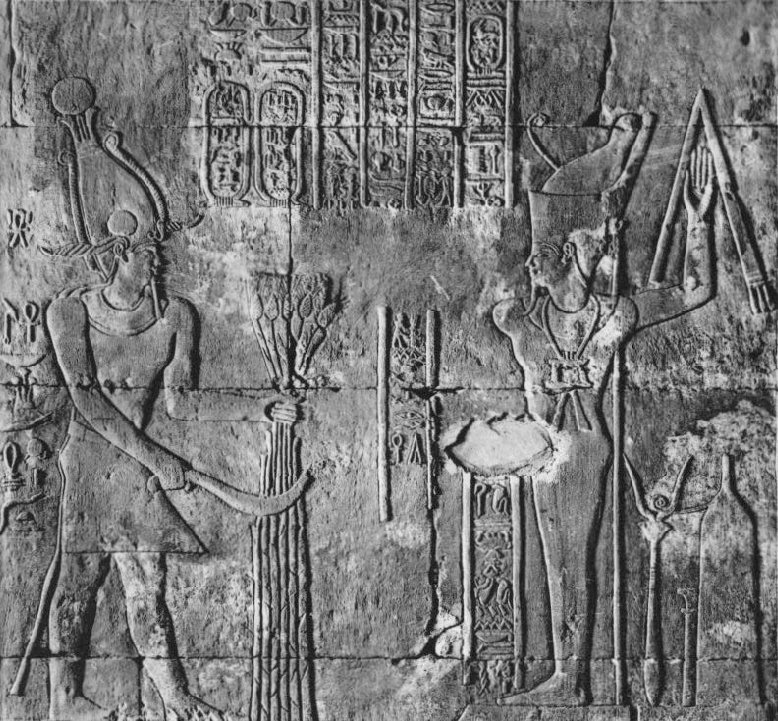

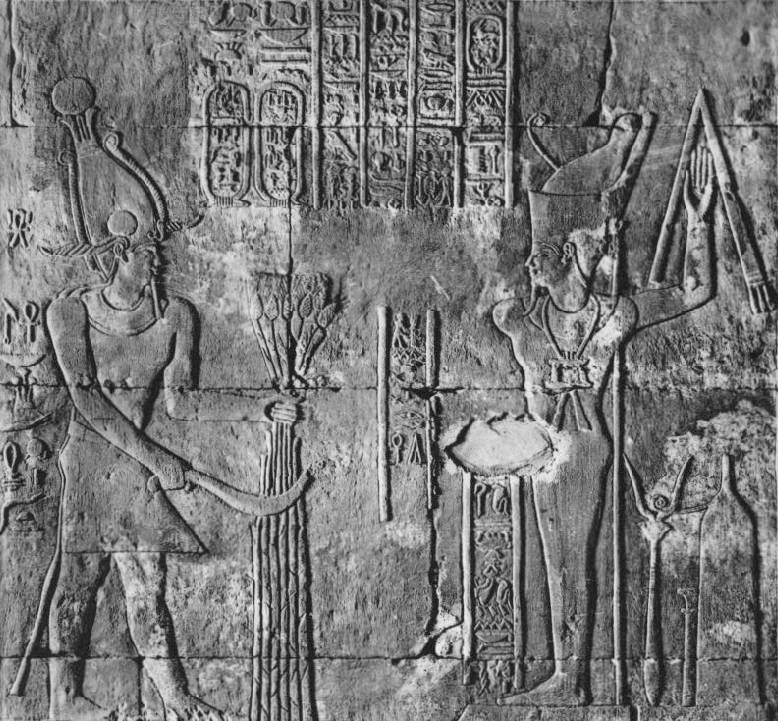

Syncretism among Greek gods was a common practice, and there was already a precedent in Egypt for combining the Egyptian gods into one entity. Apis, the bull, was regard as the incarnation of Osiris, and the two names were combined as “Osirapis.” Osirapis was worshiped throughout Egypt. Serapis was a combination of the Egyptian gods Osiris and Apis, with the attributes of the Greek gods Zeus, Helios, Dionysus, Hades and Asklepius. He was a supreme god of divine majesty and the sun, fertility, the underworld and afterlife, and healing.

The statue of Serapis

The statue of Serapis was in classical Greek style, with its iconography of Hades with a with robe. It had a Greek hairstyle and beard, and a basket of grain on his head symbolizing fertility and his connection with Osiris, the god of grain. The statue was said to be dark-blue in color and made of a combination of precious materials, including marble.

Ptolemy I constructed the Serapeum in Alexandria to house the statue. The Serapeum in Alexandria was the largest and most prestigious of all temples in the Greek quarter of Alexandria. He displayed the statue on a platform over 100 steps high. The statue was said to be was so large that each hand touched the wall on either side. It has also been written that the temple officials used clever techniques to wow visitors. One technique was a hidden magnet fixed in the ceiling above the statue, so that it appeared to rise up and remain suspended in the air. There was also a small window positioned so that a beam of sunlight touched the lips of Serapis in a kiss of renewal.

Destruction of the Temple of Serapeum and the statue of Serapis

The rise of Christian rulership in pagan Alexandria brought on ever growing tensions. According to tradition, the pagans of Alexandria dragged St. Mark to death in 68 AD. This history and the increasingly growing tensions culminated in 391 CE when the Roman emperor Theodosius I called for the strict enforcement of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire and ordered the closure of all pagan temples. The Christians desecrated the Temple of Serapeum in Alexandria and paraded its cult objects in the streets. The emperor’s orders were to destroy the serapeum since he believed that it was a source of evil, but the Christians were hesitant about damaging the statue of Serapis since they believe that doing so would bring about a major disaster. “… a rumor had been spread by the pagans that if a human hand touched the statue, the earth would split open on the spot and crumble into the abyss, while the sky would crash down at once”.

Finally, one of the soldiers, armed with a double-headed ax struck the statue on the jaw, a roar went up from both sides, but the sky did not fall, nor did the earth collapse. The Christians were delighted as rats ran out of the hollow interior and the great Serapis was revealed to be nothing more than a man-made object. Then the head was wrenched from the neck, the bushel removed and dragged off; the feet and other members chopped off with axes and dragged apart with ropes attached, and piece by piece, each in a different place, the statue was burned to ashes before the Alexandrian’s in the amphitheater.

While busts of Serapis were being destroyed throughout Alexandria, they were replaced with crosses on doorposts, entrances, columns, windows, walls, and even carved in stone in the destroyed temple of Serapis. Other temples in Alexandria were demolished in the same manner as the Temple of Serapeum, and the images of the pagan gods were melted down and used as pots and other utensils in a new church building and martyrs’ shrine. All other images and temples in Alexandria were later destroyed and replaced with crosses and churches.

Why Did the “Iconoclasts” Target These Objects?

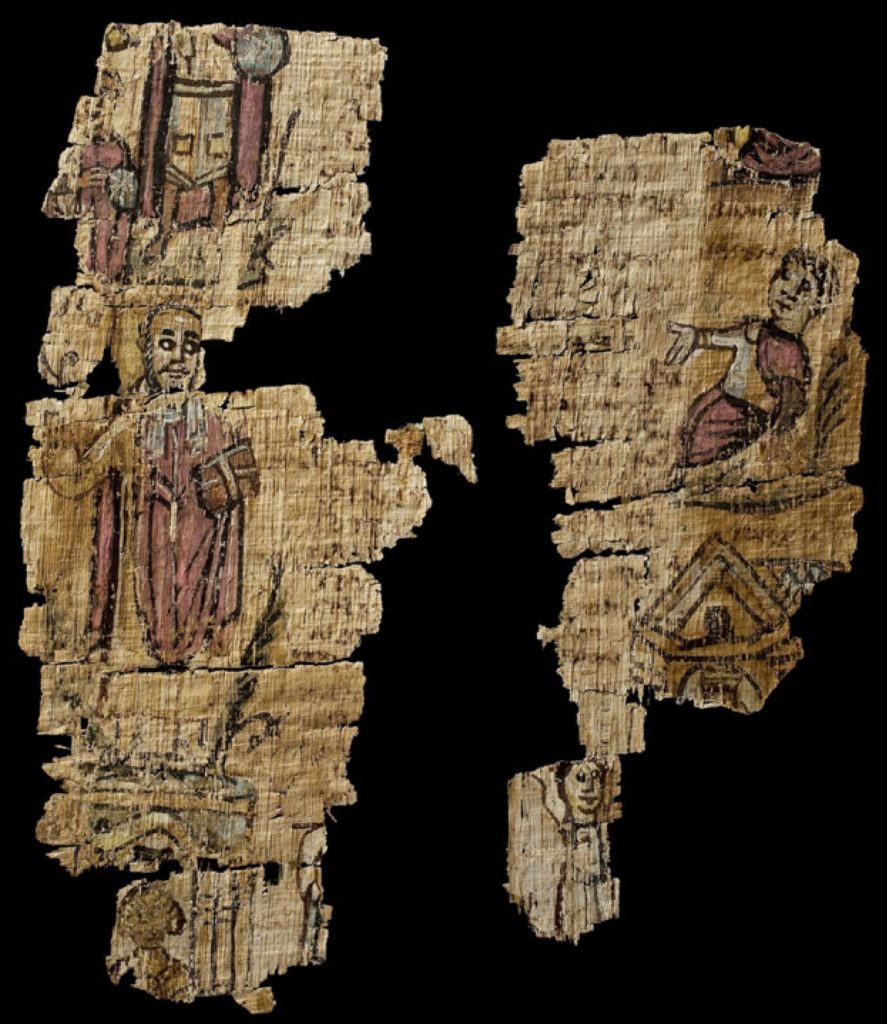

Themes of the Iconoclastic era, including representation, real presence, animation, and worship in relation to images can be traced back to archaic antiquity. The Iconoclastic period was preceded by a long history of image breaking as a legal sanction in the Roman system. The beliefs that Christianity held were inherited from polytheistic antiquity. (Elsner)

Antiquity saw a significant change in Christian attitudes to idolatry, inherited from Jewish Scripture and the complications of this problem in relation both to pagan “idols” and Christian “images.” However, historical and archaeological evidence suggests that the attacks on pagan idols by the early Christianst may not have been against pagan polytheist practices, but rather against the perceived power of pagan images. (Kristensen).

Further, Christian perceptions of bodies in stone were linked to flesh and blood bodies, and the destructive practices, including burning and selective destruction of body parts, were undertaken to negate the powers believed to dwell in pagan images. In Egyptian religion, the bodies of gods could be endlessly reproduced through representation, and mutilated just like a human body, but ultimately they could not be destroyed. For instance, Seth was endlessly tortured by Horus, but he kept reappearing in new forms. This affected the late antique Christians of Egypt methods of mutilation of the bodies of pagan gods. The careful dispersal of the fragments of the statue of Serapis in Alexandria and the countless attacks on representations of pagan divinities on temple walls are suggestive of the lengths to which the early Christian communities of Egypt were willing to go to negate the power of pagan images (Kristensen).

Evidence has also shown that the mutilation of images in late antique Egypt was linked to contemporary forms of corporal punishment and the ways that sinners were believed to be punished in the afterlife. The brutality of the judicial punishments under Constantine were known for their savagery. Mutilation of hands, feet, and genitals were well-known punishments used by Christian emperors. Further, Christian views about nudity, sex, and nude fertility figures used by the polytheistic peoples of the Empire made them objects of Christian assaults. The Christian’s mutilation of the hands, feet, and genitals of images was likely influenced by actual contemporary Christian judicial punishments. (Pollini).

Early Egyptian Christian’s notions about embodied images impacted the ways in which they physically treated images that surrounded them in temples and tombs in the late antique period. Differences in the types of destruction of images suggest that the responses were episodic and part of local circumstances, and the agency of individuals. The extensive evidence for the selective destruction of particular body parts suggests how widespread these particular ways of conceptualizing images were (Frankfurter).

References:

Amidon, Philip R. The Church History of Rufinus of Aquileia books 10 and 11, 1997, 81-82.

The Art Bulletin 94, no. 3 (2012): 368-94. (via JSTOR).

Elsner Jas. “Iconoclasm as Discourse: From Antiquity to Byzantium.”

Encylopaedia Romana- The Destruction of the Temple of Serapis http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/greece/paganism/serapeum.html.

Frankfurter, David; Hahn, J; Emmel, SE; Gotter, Ulrich. Iconoclasm and christianization in late antique Egypt: Christian treatments of space and image.

Gotter, Ulrich, Emmel, Stephen, Hahn, Johannes. From Temple to Church : Destruction and Renewal of Local Cultic Topography in Late Antiquity. Date: 2008. Ebook ebsco.

Kristensen, Troels Myrup. “Embodied Images: Christian Response and Destruction in Late Antique Egypt.” Journal of Late Antiquity 2, no. 2 (2009): 224-250. https://muse.jhu.edu/ (accessed March 18, 2019).

Nixey, Catherine.The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018. (pp. 91-93).

Pollini, John. “The archaeology of destruction: Christians, images of classical antiquity, and some problems of interpretation” in The Archaeology of Violence: Interdisciplinary Approaches, ed. Sarah Ralph. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2013: pp 241-270.

Rufinus of Aquileia, 345-410. “The Church History of Rufinus of Aquileia, Books 10 and 11 /.” Book. Edited by Eusebius, of Caesarea, Bishop of Caesarea, approximately 260-approximately 340. Ecclesiastical history. New York : Oxford University Press, 1997.

Russell, Norman. “Theophilus of Alexandria.” The Early Church Fathers. London and New York: Routledge, 2007. Pp. 222.

The Serapeum of Alexandria (VII). Iris Fernandez (2009). Published by the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World as part of the Ancient World Image Bank (AWIB).[www.nyu.edu/isaw/awib.htm]

Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames Hudson, 2003.